Lessons from Thoreau and meandering French philosophers

One day Henry David Thoreau decided to walk 216 miles from Concord Massachusetts to Staten Island, New York. As he left Concord, horse cabbies dared to ask the great walker Henry if he’d like a ride, only to be met by his scoffing laugh, “Surely, you jest! I’d rather walk!”

And so he did.

This wasn’t anything out of the ordinary for him, and he often took long walks daily, sauntering for hours and hours on end. One of his favorite Latin phrases was solvitur ambulando, which means “it’s solved by walking.”

But he wasn’t walking for fitness, nor was he captioning his latest avocado toast instagram post with step counts. We could argue that he had nothing better to do, but that doesn’t seem convincing considering he would sometimes saunter 30 miles in a day.

So, then, why did he walk?

“The walking of which I speak has nothing in it akin to taking exercise, as it is called, as the sick take medicine at stated hours — as the swinging of dumb-bells or chairs; but is itself the enterprise and adventure of the day.” — Thoreau

In other words, he was walking for the hell of it.

As many of us can relate to today, he’d get caught up in his thoughts while he was working in the village, and found that indulging in a long walk was the best remedy to get out of his own head. There was also no rush — “you must walk like a camel, which is said to be the only beast which ruminates when walking.”

Nowadays there’s hardly a situation where we’re walking without purpose or where we’re not in a rush. We’ve become obsessed with goals, a mindset that has trickled down to every corner of our lives. We have to know where we’re going.

If Thoreau were alive today to witness our rushed and chaotic lives, teleporting from point A to point B with no scenic-route option on Google Maps, we can only imagine his likely frustration and disdain for our modern “advancements.”

What Thoreau didn’t know, though, is to what extent walking without a specific purpose could bring about unique benefits — ranging from psychological, physiological and intellectual.

Let’s explore.

I. Urbanization and The Decline of Walking

- Out of necessity. Since driving and public transportation have become the norms, walking can seem like a chore at best. Recall the stories from your parents who would walk miles through rain and snow to get to school — unthinkable today.

- Walking with purpose. You know you’re better off taking the stairs than the elevator. In other words, you have a goal in mind. This could include taking a walking meeting at work, walking your dog, or choosing to walk to the park on a Sunday with a friend.

- Walking for the hell of it. Thoreau’s preferred mode d’etre, and one that we’ve slowly forgotten over time. It’s taking a saunter, just because you can.

How We Used to Walk

Anyone that has ever went from a small city to a metropolis like New York has felt the drastic difference in the pace of life. This is because people actually arewalking faster, and this can be observed in cities across the world.

Geoffrey West, author of Scale, found that the “average walking speeds increase by almost a factor of two from small towns with just a few thousand inhabitants to cities with populations of over a million, where the average walking speed is a brisk 6.5 kilometers per hour (4 mph).”

This goes on to a certain extent, of course, as we have biological limitations on how fast we can walk. But the point is clear: as our cities get bigger, we move faster.

We’re also walking less. Specifically, the average American takes about 5,900 steps a day, whereas the average in Australia is nearly 9,700, Switzerland is 9,650, and the average in Japan is 7,168. People considered to have a sedentary lifestyle take 5,000 steps and below, and those that have a very “low-activity” lifestyle take 5,000–7,000 steps.

Taking a step back in time, it’s easy to imagine that the average person was more physically active 15,000 years ago then we are today. We had to do our own cooking, cleaning, hunting, gathering, farming, balancing jugs on our heads; compare this to our current lifestyles where we can walk down the street 5 minutes to grab a coffee or just order our butter chicken curry and cheese-nan on UberEats.

But how much walking did we actually do?

While we can’t go back 10,000 years and strap pedometers to our ancestors, researchers took the next best approach; they strapped Fitbits to a hunter-gatherer tribe in Northern Tanzania, the Hadza’s. On average they found that the Hadza’s had about 2 hours of moderate physical activity daily, much of which was spent walking (foraging) on average 15 km per day.

I’m not saying that the AHA needs to revise their guidelines (not that they have a track record of making great recommendations). I also realize that it’s unrealistic to walk as much as the Hadza’s when we don’t have to — we’re not hunter-gatherers anymore and I’m sure if the Hadza’s had a choice, they’d probably drive.

That said, we have diverged greatly in the amount of time we spend doing activities that we did for most of human history, walking being a primary example. In exchange, we’ve got the wonders of modern transportation. But has modern transportation really benefited us? Of course it has — but it has its limits.

The Limits of Efficiency

Marchetti’s constant suggests that people on average spend one hour commuting (30 minutes each way), regardless of infrastructure, location, method of transportation and distance — and they’ve been doing so for hundred, or even thousands of years.

When you compare commute times between the Ivory Coast, Portugal and Boston, three very different locations, we still find that people spend about one hour commuting, regardless if they’re walking, riding the train or driving.

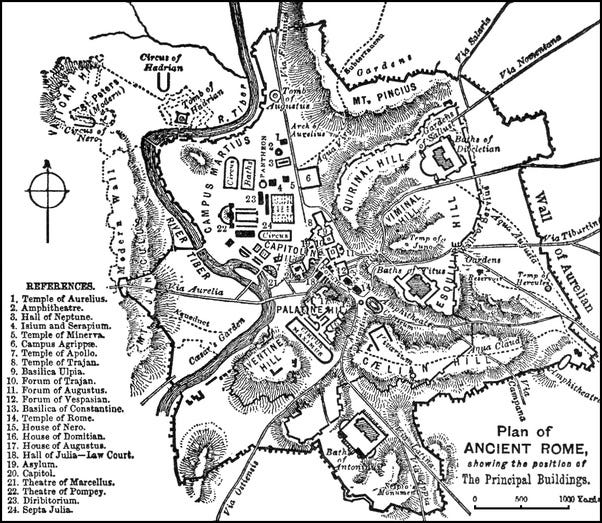

Most cities up until the 1800’s had an area of 20 km, or a radius of 2.5km, like the map of ancient Rome below. People on average walk 5km/hour, so a trek across town to meet someone, go to school, work, etc. would never take more than an hour total.

This suggests that there’s perhaps an average optimal threshold for human spatial navigation. One reason could be that we’re instinctively tribal and have a drive to say close to home, and this close-range proximity to our homes has been hardwired into our brains over millions of years — and maybe that means within a 30 minute radius.

When we push the limits that evolution has set for us, the results can be detrimental. We know that rates of depression and divorce increase with greater commute time. Robert Putnam claims that “every 10 minutes spent commuting results in 10 percent fewer social connections.” And that effect becomes pronouncedly more negative past a total of 1 hour of commuting!

This is a fascinating observation and has implications for all of our lives, as well as a reality-check for the amount of time and effort we spend working and building infrastructure to support “faster” means of transportation. It suggests that even if the Hyperloop or intercontinental flights become more accessible, and people won’t mind traveling across the country/world… it likely won’t change the average amount of time people spend commuting.

So, we’ve destroyed the earth to lay down asphalt in order to drive in steel boxes that are making us fat, which we then spend years paying off to support a ‘better’ lifestyle; but we’re still spending the same amount of time commuting.

I thought technology was supposed to save us time?

In sum…

We’ve become obsessed with prioritizing efficiency and speed, walk faster but less than our ancestors, and are suffering at the expense of an increasing ease of transportation — without as much benefit as perhaps we lead ourselves to believe.

In the process, we’ve lost touch with a basic, human activity that’s been so important for our mental, physical and intellectual health.

II. The Unique Benefits of Walking

Here’s what Thoreau didn’t know…

Walking vs. Exercise. Research has found that walking directly affects the brain’s blood supply. Now, this isn’t news: we all know that exercise increases our blood-pressure/heart rate meaning that our entire body reaps the benefits of increased circulation.

What’s worth noting about this study is it shows that the effect that walking has on the brain is more direct. Specifically, the impact of one’s foot on the ground sends a specific pressure waves rippling through the body — this acts on specific arteries by increasing the blood supply sent to the brain (which, naturally, improves brain function and cell growth in many ways).

Surprisingly, this benefit is specific to walking— although running creates a higher pressure impact, it does not have this same effect. There seems to be a mechanism related to the number of average heartbeats/minute and how syncing our steps close to that rhythm can “optimize brain perfusion, function, and overall sense of wellbeing during exercise.”

“There is an optimizing rhythm between brain blood flow and ambulating. Stride rates and their foot impacts are within the range of our normal heart rates (about 120/minute) when we are briskly moving along.”

Finally, 40 minutes of walking 3 times per week had benefits above other exercise forms (stretching, yoga, resistance training) and walking was shownto increase the size of the hippocampus, the brain’s center for memory.

Longevity. Many of us have realized that we don’t walk enough so we’ll carve out a specific time and place to take a stroll; this is healthy and we should do more of it, especially considering walking daily is one of the common denominators (along with diet, social cohesion, and a sense of purpose) in the Blue Zone societies — those regions with proportionally the highest number of centenarians and super-centenarians (those who are 100+ years old).

Weight Loss. Interestingly, clinically-tested “walking therapy” has been shown to have promising results (although more studies need to be done) when it comes to patients seeking to lose weight. Here’s a quote from a patient who underwent walking therapy:

It’s a brilliant idea that created time out of thin air by combining the appointment to which I had already committed with the exercise I wanted but didn’t think I had time for. It demonstrated the clinician’s commitment to exercise, allowed her to directly observe my ability to undertake an exercise program of moderate intensity, provided me with a sense of routes I could walk, close to work, and, most importantly, gave me ‘permission’ to take the time during the workday to walk, clear my head and raise my energy levels.

Of course running and high intensity exercise are great mood boosters too, but it can be intimidating to start with these, and they’re not accesible to everyone. Fortunately, you don’t have to “go big or go home,” — the easiest prescription is to just walk.

Mood Booster. Hippocrates, the Greek physician, described walks as “man’s best medicine” and often prescribed walks to his patients. Before we invented antidepressants, which by the way have very questionable long term effects, what did we do when we were feeling down? Most cases of depression were self-cured, meaning they went away over time. Walking is an immediate antidepressant — it’s the cheapest and easiest way to get some relief and out of your head, no extra equipment needed. I think Tony Robbins once said, “if you get in your head, you’re dead.”

Walking vs. Meditation. The idea of walking is easier to embrace and start than meditation. Meditation can feel silly, difficult, or maybe there’s just “no time” in the day. If you feel that way, then I have some good news. You don’t have to wake up at 5 am and pretzel your legs into an impossible position to meditate. You can, in fact, meditate anywhere and anytime — including during your walk.

You can try out walking meditation, which is simple. Take a stroll outside near your home or work, walking at a very slow pace. You are looking down at your feet as you walk. As you pick up one foot, consciously inhale. Setting your foot down, consciously exhale. Focus only on your breathing and footsteps. If thoughts start to pop up in your mind, refocus back on your breath.

If you’re already a meditator, you can combine walking into your routine for increased benefit. One study measured a group of 110 university students, and found that doing meditation before or after the walk helped reduce anxiety levels more than just taking a walk.

A Free Creativity Boost.From Aristotle to Charles Dickens and Steve Jobs, it’s hard to find a philosopher, writer or entrepreneur that hasn’t used walking as a tool for deepening conversations and expanding minds. In fact, according to a 2014 Stanford study, walking can make you up to 81% more creative.

I remember when I was a manager I loved to get out of the stuffy rooms and take walking-meetings with my teammates. It was trickier to do this with more than two or three people, so I usually kept the promenades uno-a-uno. We didn’t walk for very long, maybe about 20–30 minutes or so, but it was always rejuvenating. After our minds were stimulated we’d end the walk at a small park and chat for another 15 minutes. This is when the juices were flowing and the conversations were hardly ever dull. Much better than being back in the office falling asleep at our desks.

Urban vs. Nature Walking. Studies show talking walks in nature is, not surprisingly, very healthy, and the research on this is so strong that it’s influenced city planning and architectural policy to create more ‘green space’ in cities.

While adding green space is a good step, urban walking (just walking around in the city!) can also be incredibly productive, possibly in different ways. In the 1950’s, French philosopher Guy Debord wrote a famous essay on the critique of urban landscapes, and proposed the idea of psychogeography,which focuses on discovering forgotten aspects or paths less traveled in the city and the effects that has on the individual.

Guy started arranging groups he called “dérives,” (French for “drift”) which were basically long, meandering walks around Paris. Dérives were described as “an unplanned journey through a landscape, usually urban, in which participants drop their everyday relations,” and “let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.”

Perhaps the French idea of a “dérive” sounds more romantic than Thoreau’s sauntering, in which case we can take inspiration from Guy’s terminology and roll with it. As long as we’re getting out of the house and walking somewhere, anywhere.

I Love to Walk, Too

I’ve recently rediscovered the joys of walking — not to work — but under a set of slightly different circumstances. In the past year I’ve developed a practice of doing 5-day water fasts. While it is very difficult, especially in the first couple of days, I find that it improves my mental clarity tremendously and has the added benefit of acting as a sort of ‘reset’ button for the immune system.

So, I throw on my podcast, comfortable shoes, and stroll around Tokyo for a few hours. Walking is a great antidote to the initial feeling of unease when fasting, and it’s a nice way to observe and take the scenic routes — a much needed break from the hasty, quickest-route-possible lifestyle that’s so prevalent.

When I’m walking for more than 30 minutes — fasting or not fasting — I get a lot of ideas popping up into my head. In fact, I wrote about 30% of this blog post using the speech-to-text function on my iPhone during a long stroll around Tokyo. Technology, while a distractor, can also facilitate creativity during our walks.

A Subtle Shift in Perspective

We have the choice to drive, fly and get where we want at unprecedented speeds, and society reinforces the belief that we should be going places in a certain way. We should pause and ask what affect our routines have had on our lives and what changes we might need to make.

We don’t have to detach from the modern necessity of purposeful walking — nor could we if we wanted to. We still have to go to work and get from point A to point B, and it’s great that we consciously choose to take the stairs instead.

But we can certainly take a moment to appreciate Thoreau’s saunters and his walks without purpose. We no longer have to ask, what’s the point, Thoreau? In light of all of the benefits of walking that we’ve explored, we don’t need a reason to walk.

It simply requires a subtle shift in perspective from a goal-oriented mindset to a doing for the sake of doing mindset — in other words, just going for a walk.

How To Walk For The Hell Of It

I encourage you to reflect on how much walking you do now, and give yourself the freedom to walk more. Get away from the idea of trying to make it productive and perhaps you’ll discover the simple joy, or adventure, of taking a stroll without purpose.

Here are some ideas to get you started.

- Try walking without any other sort of stimulation — no talking, audiobooks or music. Don’t pick a route. Just walk for an hour or two or three or ten.

- Next, switch it up. Try walking while listening to music or a podcast. Or go for a long walk with a friend, or turn an acquaintance into a friend over a walk. Go for an early morning walk or an evening walk.

- Nature walking. Parks, mountains, green spaces. Explore, conquer, sit, plan or don’t plan, it’s up to you. Try not to bring your phone. Get excitedabout a mountain.

- Urban walking. Take the route less traveled. If you’re in Paris, use a map of London. Maybe even try out geocaching.

- Organize a purposeless walk in your city or wherever you are. Call it a Thoreau Saunter or a Dérive. These are due for a revival. Oh, there’s an app for that (the dérive app).

- And by god, don’t measure your steps. Some things don’t need to be measured.

Readings and videos that inspired this post:

BECOME A SUBSCRIBER

The word ikigai roughly translates to “the reason you wake up every morning” in Japanese. You could call it an intrinsic motivator, passion, or whatever.

Right now, my ikigai is writing. I’ve discovered, forgotten, and re-discovered this interest a few times, but I keep getting pulled back. And now I’m writing full time.

I’m not writing for any media outlet or publisher, and I publish all my articles and eBooks as an independent author on my blog and across the web. That means I don’t have to worry about trying to appeal to a mass audience or selling ads. It gives me the freedom to say what I want and write whatever I think would actually be useful to…you, the reader.

Perhaps you’ve found one of my articles useful, motivational or shared them with others. Perhaps one small piece of information I shared saved you time or money, or helped in some way. Maybe you thought, “hey, thanks for writing that!” If so, then consider becoming a monthly subscriber.

If you’d like to support my work you can do so through donating through Patreon. Just click on “become a patron” below.

Of course, you get some rewards. A $5/ month subscription gets you…

- Access to exclusive articles on my site. I research and deep dive into various niche topics, as well as those requested by readers.

- My monthly “Ask Me Anything Q&A.” You can literally ask me anything (the weirder the better). I select the most popular questions and write up well-researched answers.

- Early drafts of my articles. I share my work as I’m researching and writing it, for those interested in my creative process.

SUBSCRIBE BELOW

How it Works:

- Choose how much you’d like to pay. You can choose to pay as little as $1 per month. To get access to the above rewards you need to pledge a minimum monthly $5 donation.

- Choose your payment method. Credit card or PayPal.

- Done! Once your account is created you’ll gain access to the subscribers-only section on my site.

…OR MAKE A DONATION

This Post Has 3 Comments

Babak Fakhamzadeh

28 Jul 2018Nice article!

I’d appreciate it if you source the derive app graphic you use. (The one where the guy walks on a background that resembles a map.)

Cheers!

Olga Yurchenko

7 Aug 2018Love your article!

Misha

12 Aug 2018Thanks!